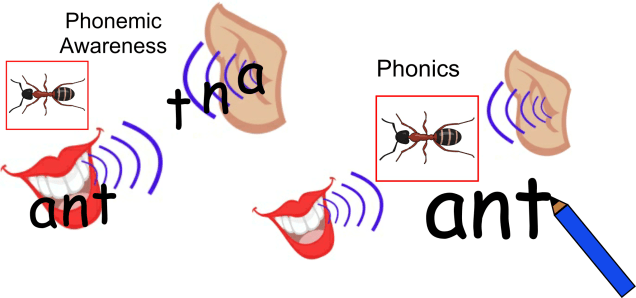

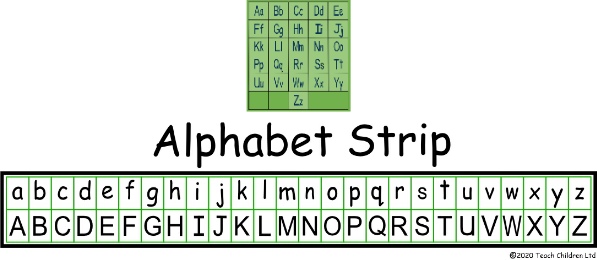

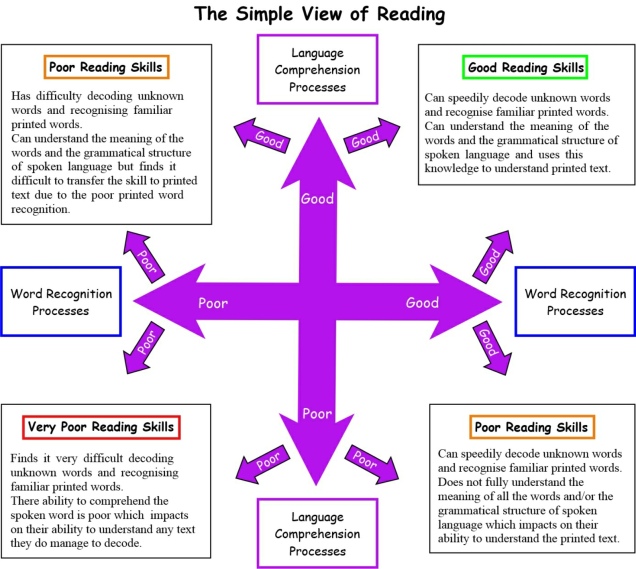

Learning to hear and differentiate the vowel sounds from consonant sounds is an important skill in understanding how words are formed. Every word in the English Language has to have a vowel sound in it and every syllable in a word also has to have a vowel sound within it. This knowledge is an important element in developing our phonemic awareness and phonics knowledge as we start to learn how to read and spell words.

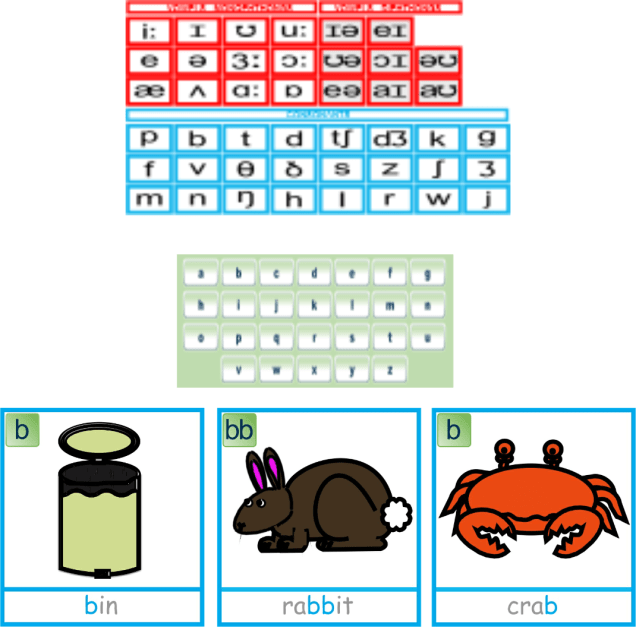

There are 20 vowel sounds in the English (UK) Language, usually (in the UK Education System) split into two main categories based on sound quality:

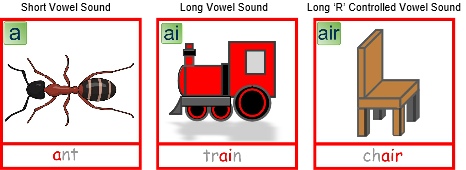

- ‘Short’ vowel sounds, due to the short duration of the sound being made, the sound cannot be held onto without becoming distorted, such as the /e,(e)/ in me, pea and tree

- ‘Long’ vowel sounds, due to the length of their pronunciation, these can often be held without distorting their sound, such as the /oi,(ɔI)/ sound found in the words :boy, coin and buoy

Here at Teach Phonics we split the ‘long’ vowel sounds category into ‘long’ vowel sounds and ‘long ‘R’ controlled’ vowel sounds. The ‘long ’R’ controlled’ vowel sounds are so called because of the slight /r,(r)/ sound quality that can be heard in them for example the /or,(ɔː)/ sound found in the words: fork, door, walk and sauce.

The English Phoneme Chart (https://www.teachphonics.co.uk/phonics-phoneme-chart.html ), which uses the unique symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), splits the 20 vowel sounds into two groups based on mouth position:

- Monophthongs which have one mouth position throughout the sound for example /e,(e)/ in me.

- Diphthongs, where the mouth position changes, giving a 2 sounds quality to the phoneme for example, /oi,(ɔI)/ in boy.